I do think this case is a watershed in Civil Liberties, Free Speech and Freedom of the press. The Case recently which Mr Robinson ( Yaxley Lennon) brought against Cambridgeshire police, on another matter similarly saw the appointment of a “Special Interest” Judge and a similarly tainted verdict. The Language choices in the judgement are Pertinent to a subtext of authoritarian condescension, even by the arcane standards of Legal Language any independent observer can grasp the sneering tone and incredulity in the written words, should one attend a reading of the judgement in person I am sure it would be redolent of Peter Cook in Drag.

I will do a fuller analysis after the sentencing hearing tomorrow for which I will obtain a transcript before taking a scalpel to this Ongoing travesty of Justice.

The Nepotistic establishment stitch-up can be seen early on Both The Judge in the Case and Leading Counsel for the AG Hail from the same Chambers.

Caldecott is Head of the Chambers from where the Judge Worked before becoming a Judge? https://web.archive.org/web/20081220155146/http://www.onebrickcourt.com/barristers.asp?id=24

https://web.archive.org/web/20090515185649/http://www.onebrickcourt.com:80/barristers.asp?id=25

| https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/court-of-appeal-home/coa-biogs/ | |

Dame Victoria SharpDame Victoria Sharp was called to the Bar (Inner Temple) in 1979. She became a Recorder in 1998-2008. She was appointed as a Justice of the High Court in 2009, and was assigned to the Queen’s Bench Division. She was a Presiding Judge on the Western Circuit from 2012 to 2013. She was appointed as a Lady Justice of Appeal in 2013. She was appointed as the Vice-President of the Queen’s Bench Division in January 2016, and President of the Queen’s Bench Division in June 2019. |

|

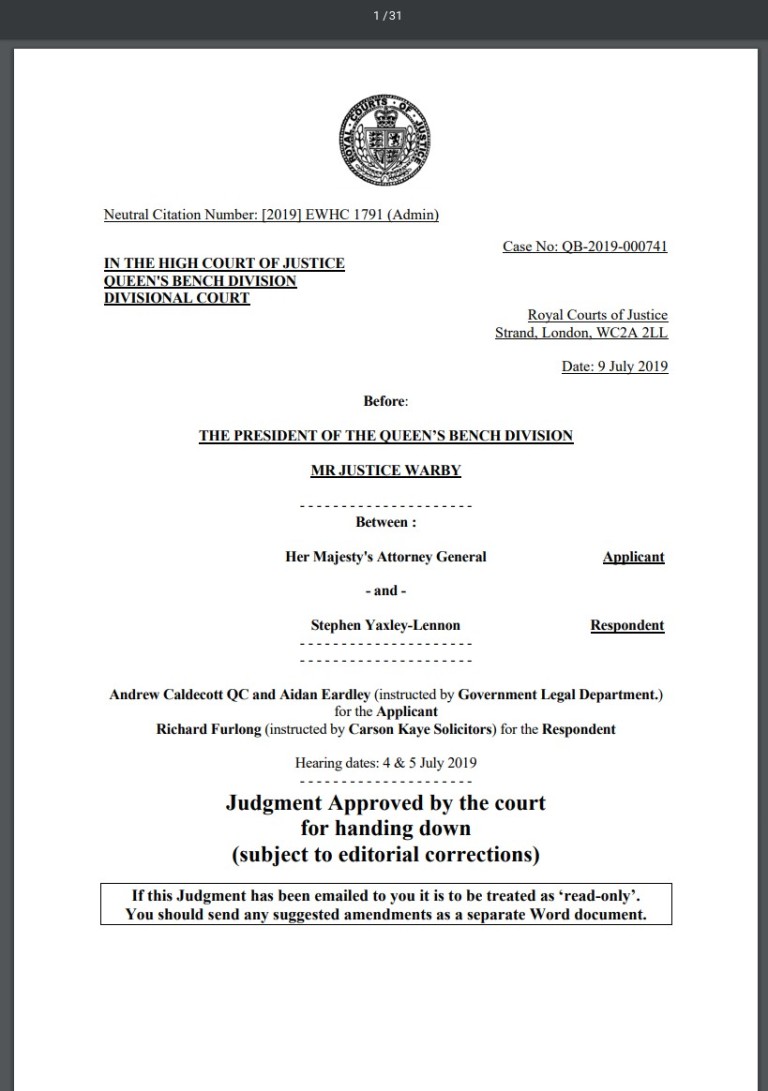

The Judgement in Full

https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/ag-v-yaxley-lennon-jmt-190709.pdf

para 24 p.7

” During the hearing, the respondent submitted a further affidavit (his third)”,

para 35 p.11.

The evidence suggests, however, and we find, that two months after the order was made the relevant information had not been inputted into CREST. This is a regrettable departure from standard practice, which is accurately described in the guidance issued by the Judicial College (Reporting Restrictions in the Criminal Courts 2015 (revised May 2016)) at para 5.1: “any reporting restriction is shown on the Crown Court list under the name of the relevant case – allowing a ready means of checking whether there are such restrictions in place”.

38. We have viewed the Video, and an agreed transcript is in evidence. The content of what was said, done and broadcast is central to this case. We will need to consider it in some detail when we come to the specific allegations of contempt.

Point 8 page 13 AG’s Case. (8) At another point, the respondent incited viewers to harass the criminal defendants. The words relied on are:- “You want to harass someone’s family? You see that man who was getting aggressive as he walked into court, the man who faces charges of child abduction, rape, prostitution – harass him, find him, go knock on his door, follow him, see where he works, see what he’s doing. You want to stick pictures online and call people and slander people, how about you do it about them?”

44. p.14 introduction respondents (<i> Tommy/Stephen</i>) case? The respondent’s most <blockquote>recent affidavit</blockquote> provides some further responses to the Attorney General’s specific points: ( <i>Italics ED</i>.)

47. Mr Caldecott argues that the actus reus of this offence is committed by the reporting in and of itself. The fact, if it be so, that some information is in the public domain has no bearing on the question of whether an act of contempt has been committed. As to mens rea, he submits that negligence may be sufficient but in any event subjective recklessness as to the existence and terms of the RRO is enough as a matter of law.

48. Mr Furlong accepts that breach of a s 4(2) order is capable of amounting to contempt. In his skeleton argument, he made four main submissions as to the law. First, he argued that contempt of this variety can only be made out on proof of “disobedience to an order of the court properly made”. Secondly, he invited us to conclude that on a proper analysis this RRO was not “properly made”. Next, he argued that contempt cannot be made out unless it is proved that the respondent had knowledge that an order was in force, postponing publication; it is not enough to establish reckless in that respect. He <b>Draft 9 July 2019 10:45 Page 15 </b> High Court Unapproved Judgment: AG v Yaxley-Lennon [2019] EWHC 1791 (Admin) further argued that it would be wrong to import recklessness into this branch of the law at all.

p.18

57. In our judgment, therefore, it is enough to establish <b>subjective recklessness</b>, as defined in R v G [2003] UKHL 50 [2004] 1 AC 1034. A person who publishes material in breach of an RRO will be guilty of contempt if he or she foresees the possibility that the publication may be a breach of such an order, but proceeds with publication, taking an unreasonable risk. Someone who knows or suspects that an order is in place but does not know its terms is clearly put on inquiry. If the person makes no enquiry, or fails to take reasonable steps to find out what the terms are, it will ordinarily be easy to infer <b>subjective recklessness. </b>

59. As it is, we reject the respondent’s evidence that he looked online and that he and a colleague looked at screens and the court door, to see if an order could be found. This is an account that, if true, one would expect to have featured prominently at some stage before it was first advanced in the witness statement the respondent submitted in the proceedings before the Recorder of London on 22 October 2018, many months after the event (for example, before the CACD). 60. The version of events the respondent has now put before us is more elaborate still, adding significant details that were not mentioned before.

Breach of the strict liability rule

69. In support of these arguments, the Attorney General relies in particular on the passage in the Video that we have aleady quoted, which is characterised as an incitement to the respondent’s supporters to harass the defendants. Because of its importance to this part of the case, we repeat the passage: “You want to harass someone’s family? You see that man who was getting aggressive as he walked into court, the man who faces charges of child abduction, rape, prostitution – harass him, find him, go knock on his door, follow him, see where he works, see what he’s doing. You want to stick pictures online and call people and slander people, how about you do it about them?”

70. Mr Caldecott also relies on what he submits are the “abusive and emotive terms of the Video” generally which can best be gauged by looking at the Video itself. Examples of this are the following:

top of page 20

[p40] “just trying to show people who are watching this is what’s happening, this is what the case is this is how many girls were victims. This is what they’ve said and this is what they’ve done [male bystander] Dirty bastards innit. [Respondent] Yeah mate. [female bystander] Should fucking hang him …”

p.23

75. The respondent says his words were not intended to encourage his followers to harass the defendants but rather to denounce the media for their behaviour towards him and others. However the issue raised by the application is the meaning and effect of his words. In our judgment, those words and the manner of their delivery were an encouragement to others to harass a defendant by finding him, knocking on his door, following him, and watching him, and this gave rise to a real risk that the course of justice would be seriously impeded. A little later in the Video, the respondent asked viewers rhetorically why there were not dozens of national media outside court waiting and “why are they not trying to approach these criminals or show where they live or show where they work or show what they’re doing or why why why why …?” All of this has to be assessed in the context of the Video as a whole, in which the respondent approves and encourages vigilante action. <b>We are sure that what the respondent said in this passage will have been understood by a substantial number of viewers as an incitement to engage in harassment of the defendants. </b>

76. …. Further, the medium matters, as well as the message. The dangers of using the un-moderated platforms of social media with the unparalleled speed and reach of such communications, are obvious. In this case, the respondent was engaged in the agitation of members of the public in respect of what he presented as a serious threat to society. His words had a clear tendency to encourage unlawful physical or verbal aggression towards identifiable targets. Harassment of the kind he was describing could not be justified. It is not necessary to assess the level of risk that such conduct would in fact be engaged in, beyond concluding that it was real and substantial. Furthermore, there was plainly a real risk that the defendants awaiting jury verdicts would see themselves as at risk, feel intimidated, and that this would have a significant adverse impact on their ability to participate in the closing stages of the trial. That in itself would represent a serious impediment to the course of justice.

p.24

Direct interference with the administration of justice

78. The Attorney General’s case is that two aspects of the respondent’s conduct amounted to contempt at common law, because <b>they involved interference, or created a real risk of interference, with the administration of justice</b>. The first is his conduct in confronting some of the defendants, and one other person attending court “<b>in aggressive and provocative terms</b>” and openly filming them “<b>so that they would know that these encounters were likely to be made available to the public via social media</b>”. The vices of such behaviour are identified as (a) the creation of a real risk that those defendants would not attend Court in a frame of mind that allowed them to participate properly in their trial and (b) disrespecting the authority and dignity of the court and the administration of justice, “which require that persons who are required to attend court should be able to do so without let or hindrance or <b>fear of molestation</b>.” As will be apparent, there is a degree of overlap between this aspect of the Attorney General’s case and the strict liability limb, with which we have just dealt.

79. We find that the respondent’s conduct did give rise to a real risk that the defendants he confronted would arrive at Court in an upset and agitated state, unsuitable for participation in the serious proceedings in which they were due to take part. <b>The true nature of the respondent’s behaviour when confronting the defendants outside court can only be properly appreciated by viewing the Video</b>. It can properly be characterised as of an intimidating nature, and “aggressive and provocative”. We agree with the submissions made on behalf of the Attorney General.

82. This brings us to the second aspect of the respondent’s conduct that is said to amount to common law contempt: “taking photographs of persons while they were entering the Court building (or the precincts thereof), and [simultaneously] publishing those photographs, which are administration of justice offences contrary to s41 of the Criminal Justice Act 1925 and, in the circumstances of this case, contempt of court at common law meriting committal proceedings.” Again, it is right to recognise a degree of overlap between this and other aspects of the Attorney’s case, but this remains a separate and distinct ground.

85. ……. There is threshold of seriousness which the Attorney General must surmount: a s 41 offence is not in and of itself a contempt of court. The question should be approached as one of substance: did the respondent’s conduct in filming the defendants as they arrived at court and simultaneously broadcasting the footage interfere so significantly with the due administration of justice as to go beyond mere disobedience to the statutory ban on photography, and justify the more severe sanctions attaching to contempt of court?

86. This is essentially a question of fact and degree, for the Court’s evaluation. At one end of the scale may be the actions of a foreign tourist, taking pictures of the courtroom scene purely out of interest in the architecture or design of the interior, in ignorance of any rule against doing so. Towards the other end would be the recording and online publication of a video of sentencing remarks, in deliberate contravention of a welladvertised prohibition on filming in court, accompanied by derogatory comment, as in Cox. In our judgment, the filming here went beyond mere contravention of s 41. It crossed the threshold of seriousness, and justifies the imposition of sanctions for contempt.

87. We would identify the following factors, considered cumulatively: (1) This was targeted behaviour, not incidental filming; (2) it was engaged in at what the defendant must have known to be a time of high anxiety for the defendants, when they were entitled to be presumed innocent; (3) knowing that the defendants did not wish to be approached; he had attempted it before, at Huddersfield Magistrates’ Court; (4) when the respondent’s approach predictably elicited aggressive responses, he sought to exploit these against the defendants by implying that they were incriminating; (5) this was done very publicly, in a way that was likely to and did attract the attention of passers-by; (6) the filming was persistent, and involved a degree of following, whilst live streaming. The filming must of course be assessed in the context of the harassment with which we have dealt already. It is also necessary to have regard to the wider context. If the court were to condone the live broadcast of these defendants being aggressively confronted as they arrive at court, in conjunction with prejudicial commentary and exhortations to engage in harassment, it would pose a risk to the wider interests of the justice system.

<i><b>Grant of Permission ( Human Rights , and Threshold. Aspects. (ED.) </b></i>

100……But they too are proceedings brought by a disinterested public authority, the aim of which is to protect the administration of justice. There is no case that holds, in any context, that a Law Officer must show a strong prima facie case in order to pursue committal. The Court will of course examine the case advanced by the Attorney General. It will consider the public interest. It will not grant permission to pursue any grounds which appear fanciful, fail to disclose a reasonable basis for committal, or are for any reason an abuse of the court’s process. In our judgment, it is unnecessary and would be undesirable to import the test of “strong prima facie case”, and to subject an application of this kind to a preliminary vetting on its merits. We note that in Solicitor General v Holmes at [45] this Court identified the applicable threshold as a “prima facie case” and observed that “detailed consideration at the permission stage about the precise strength of the application to commit for contempt in the face of the court are to be discouraged.” We take the same view about applications of the kind before us.

Reasons for granting permission

102. Mr Furlong did not seek to persuade us that any of the Attorney General’s allegations of contempt lacked a reasonable basis in fact or law. Nor did he submit that these proceedings represent an abuse of the Court’s process. He advanced two main arguments in opposition to the grant of permission. First, under the heading “Delay, proportionality and the public interest”, he pointed to the history of the proceedings, the length of time that had passed since the original incident, the respondent’s incarceration, and the adverse impact of those matters on the respondent’s health and wellbeing. Secondly, he pointed to differences between the three grounds now relied on and the allegations of contempt that had previously put forward, and questioned whether it was fair and in the public interest to allow the Attorney General to advance the new, and modified case. 103. We did not find these submissions persuasive. Mr Dein QC had submitted to the CACD on behalf of the respondent that since he had served the equivalent of four months Draft 9 July 2019 10:45 Page 30 High Court Unapproved Judgment: AG v Yaxley-Lennon [2019] EWHC 1791 (Admin) No permission is granted to copy or use in court imprisonment the matter should not be remitted. The court disagreed, on the basis that the sentence might be longer if a finding was again made against the respondent, and a determination of the underlying contempt allegations would in any event be in the public interest: see [78]. We shared that assessment. We considered events since the hearing in the CACD, and reviewed the medical and other evidence before us, but did not consider that these materially affected the conclusions reached by the Court of Appeal. It is true that the case now advanced by the Attorney General differs in some respects from the way the contempt allegations have been put before, but we did not see any unfairness in that. We were unconvinced by Mr Furlong’s that the case as now put might divert the case into a political rather than a legal assessment of the respondent, his conduct, and that of his supporters. In our judgment, the case raised important issues about how the law of contempt applies to those who seek to report and comment on criminal proceedings and, in particular, how they conduct themselves in and near the courts.

Tommy Robinson and the Contemptible Politicisation of Freedom of the Press.

https://longhairedmusings.wordpress.com/2019/07/10/tommy-robinson-and-the-contemptible-politicisation-of-freedom-of-the-press/

I do think this case is a watershed in Civil Liberties, Free Speech and Freedom of the press. The Case recently which Mr Robinson ( Yaxley Lennon) brought against Cambridgeshire police, on another matter similarly saw the appointment of a “Special Interest” Judge and a similarly tainted verdict. The Language choices in the judgement are Pertinent to a subtext of authoritarian condescension, even by the arcane standards of Legal Language any independent observer can grasp the sneering tone and incredulity in the written words, should one attend a reading of the judgement in person I am sure it would be redolent of Peter Cook in Drag.

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

https://swarb.co.uk/regina-v-horsham-justices-ex-parte-reeves-note-qbd-1980/

https://www.judiciary.uk/you-and-the-judiciary/going-to-court/court-of-appeal-home/coa-biogs/

Dame Victoria Sharp

Dame Victoria Sharp was called to the Bar (Inner Temple) in 1979. She became a Recorder in 1998-2008. She was appointed as a Justice of the High Court in 2009, and was assigned to the Queen’s Bench Division. She was a Presiding Judge on the Western Circuit from 2012 to 2013.

She was appointed as a Lady Justice of Appeal in 2013.

She was appointed as the Vice-President of the Queen’s Bench Division in January 2016, and President of the Queen’s Bench Division in June 2019.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your hard work and for keeping a watching eye on what is going on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Alison, I think the Robinson/YaxleyLennon Case is incredibly important, the News Papers are all piling in on Him and collectively killing of the free speech of the rest of us. My own Political stance could not me more diametrically opposed to Robinson/Lennon on Israeli Apartheid, also on the Religous aspects of Islam, although I agree with him completely on the Cultural and Political aspects of Islamism and Salafi/Wahabi doctrine. On Free Speech I stand and Fight at Tommys/Stephens Shoulder also against the Rapists and Paedophiles be they high and mighty, Black or white rich or poor I hate Nonses! and as with most people from a working Grass background, I am happy to call a spade a fucking shovel ( Excuse the French)

LikeLike

LikeLike

https://www.casemine.com/judgement/uk/5a8ff8d060d03e7f57ecdbb5

LikeLike

LikeLike

https://swarb.co.uk/regina-v-horsham-justices-ex-parte-reeves-note-qbd-1980/

LikeLike

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victoria_Sharp

Dame Victoria Madeleine Sharp, DBE (born 8 February 1956), styled The Rt. Hon. Dame Victoria Sharp DBE, is the President of the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court in England and Wales.

She is the daughter of Lord Sharp of Grimsdyke[2].

Educated at North London Collegiate School and the University of Bristol, Victoria Sharp was called to the Bar, Inner Temple in 1979. She became a Recorder in 1998 and was also a made a QC in 1986.[3][4]

She was appointed Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE), as is customary, on her appointment as a Justice of the High Court on 13 January 2009.[5]

She was Presiding Judge of the Western Circuit from 2012 to 2013 and was appointed a Lady Justice of Appeal in 2013[6]. She became Vice-President of the Queen’s Bench Division on 1 January 2016, succeeding Sir Nigel Davis. She became President of the Queen’s Bench Division from 23 June 2019[7]. This appointment followed the retirement of Sir Brian Leveson on 22 June 2019[8].

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLike

https://dissenter.com/comment/5d27236860edb91ec2e00198

LikeLike

LikeLike

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLike